Password Managers as a Phishing Mitigation?

As the days wind down into the single digits before the next Mozilla All Hands in San Francisco, I’m forcing myself to think long and hard about the type of messaging we want to share with those who will attend a session we’re hosting on phishing. There’s lot of newer options coming to bear (such as webauthn) and the more angles we attack this risk from, the more successful we will be at excuting our mission.

As much as it may seem compulsory to suggest a password manager to a user for all the typical reasons (unique passwords, strong passwords, and encrypted passwords), we’re trying to derive even more value for our users to include phishing mitigation strategies. If past internal phishing engagements are any signal as to what might cause a user to stop and take a second look, it is most often a result of their password manager not presenting that familiar “hint” as to which credential goes to that particular site.

I personally use 1Password, and will be using that for example purposes in this post, but I suspect other password managers likely have familiar behaviors that can serve as a signal to users when something isn’t quite right.

Credential Hints

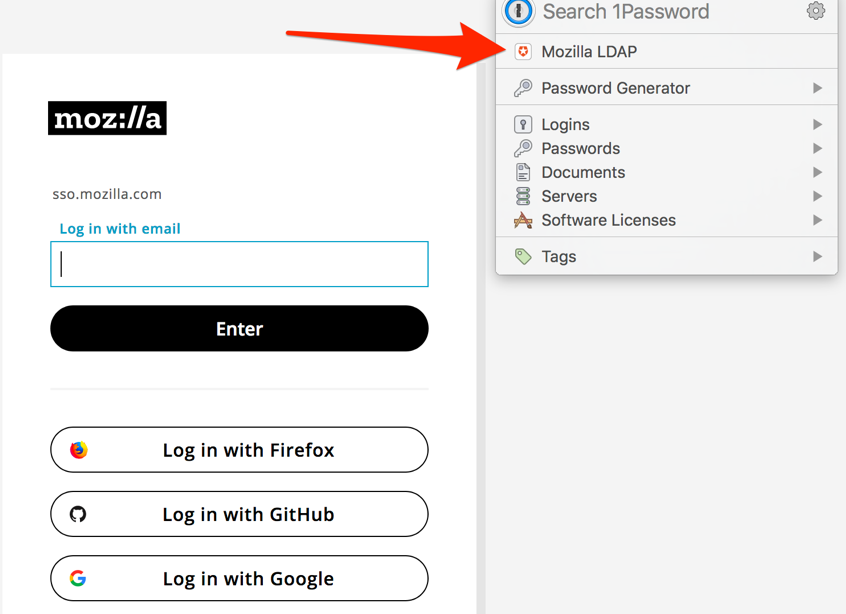

So, let’s say you’re using 1Password and your using the 1Password Firefox Add-On. You’ve got a website, like Mozilla’s auth0 SSO integration, which then prompts you for auth. Within your browser add-on you will be presented a hint, like so…

You might wonder how the password manager knows to present you that credential hint, but it’s via a capability I personally refer to as “URL bindings”.

URL Bindings

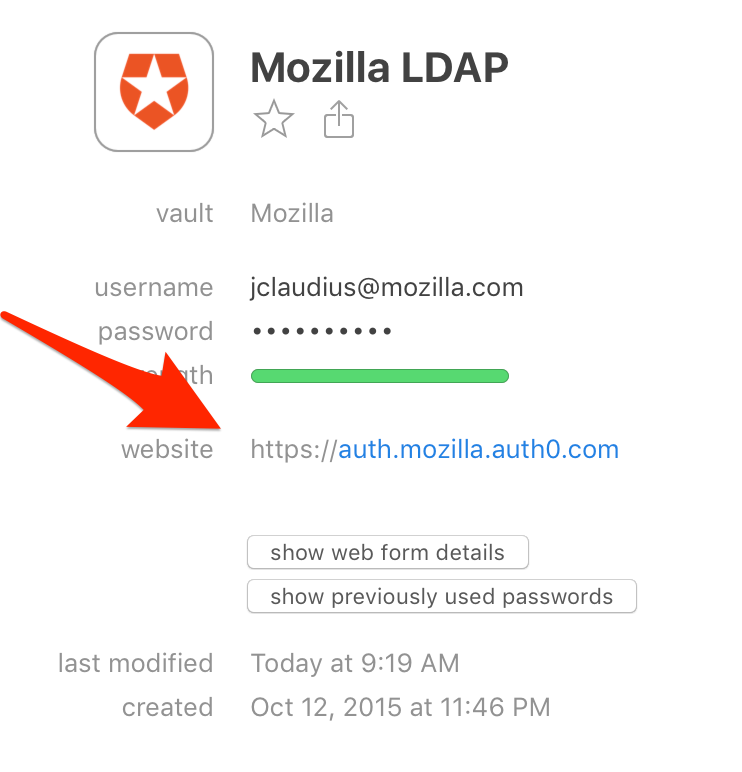

“URL bindings”, as I call them, likely have somewhat different phrasing based on the password manager, but it’s often just a URL attribute associated with the credential entry so that when you visit said website that the password manager can present an intelligent hint. In 1Password, such a URL binding looks like so…

How could this help stop password phishing?

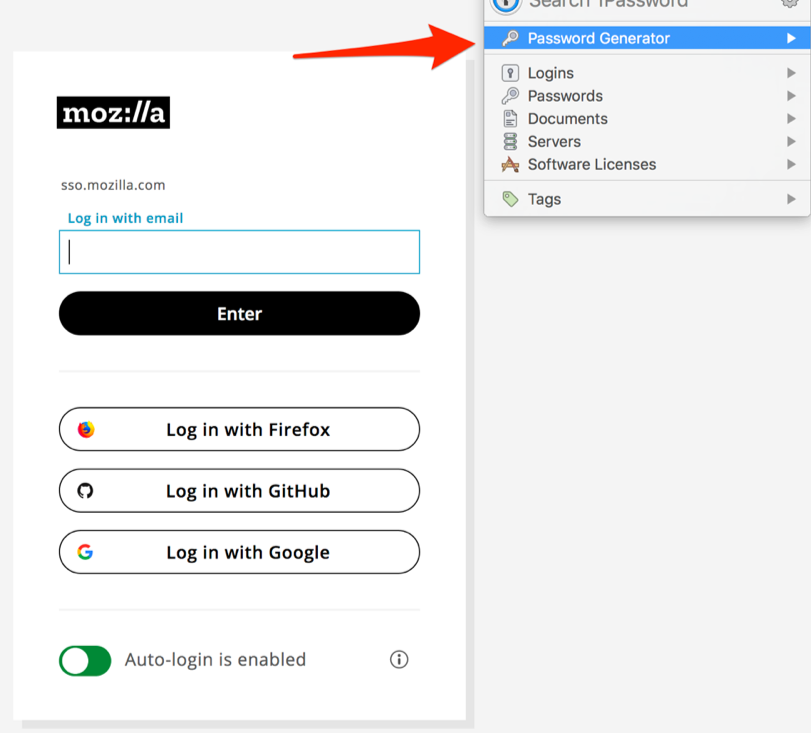

As noted above, one of the most common methods we’ve observed for users to quickly identify phishing sites (both internal and real-world) is through the lack of a credential hint in the password manager. It’s simple, but it is often a tell-tale behavior change that is noticable that users often pick up on. So, if someone was to say clone our familiar login page and try to phish a user who is familiar with such a behavior expectation they would see the lack of a hint, like so…

If you can help train users to depend on such a matching behavior that could serve to reduce the risk of them inadvertently leaking their credentials to a phishing site. However, there are potential corner-cases to be aware of here.

Partial Matching Pitfalls

As much as it is my hope that all password managers would (or would someday) treat “URL bindings” with absolute strictness, this is often not the default behavior. In fact, rather than this being considered a bug, it’s more likely to be touted as a feature. For instance, if you have two websites, say foo.example.com and bar.example.com it might be likely that those sites share a common authentication scheme. So a user who’s been to foo.example.com and registered credentials for that website, will likely end up with a hint to use those credentials on bar.example.com.

However, it could be possible for an attacker to abuse such a behavior in a case where the websites authentication provider is also a shared hosting provider, such as Auth0. So, if the real website was say foo.auth.auth0.com (owned and operated by foo organization) and the phishing website was say foo-login.auth.auth0.com (owned and operated by an attacker) it is possible that a user trained using such a hint-based strategy could be fooled into leaking their credentials for foo organization to an attacker squatting on foo-login.auth.auth0.com.

A possible fix for such a pitfall could be working with the shared hosting provider to get an organization specific custom domain (such auth.foo.com) and that would help prevent such an attacker from easily squatting an adjacent subdomain within the same parent domain. That leaves subdomain takeovers on the parent (something I’ve discussed in other posts 1,2,3), but perhaps that is not as easy for an attacker to do if you have good processes and strong DNS controls in place.

Conclusions

So, to circle back on the original question of whether a password manager is useful as a phishing mitigation? I would have to say “yes”, it’s helpful in preventing phishing attacks if the alternative is a user who could be easily convinced to manually leak their credentials to any phishing site. At the very least this helps reduce the threat population and gets us a little bit further down the road than asking users to simply memorize what domains are ours and which domains are not.

Lastly, as I hinted to above, I think this is an amazing space for password manager providers to innovate and I’d be very interested in hearing how password managers could play a bigger role in password-based phishing mitigations.